The Need for Guidance

Over the past few years, we’ve seen AI-generated content move from experimental research in computer science labs to one of the engines of digital content creation.

Synthetic media provides significant responsible, creative opportunities across society. However, it can also cause harm. As the technology becomes increasingly accessible and sophisticated, the potential harmful, as well as responsible and beneficial impacts, can increase. As this field matures, synthetic media creators, distributors, publishers, and tool developers need to agree on and follow best practices.

With the Framework, AI experts and industry leaders at the intersection of information, media, and technology are coming together to take action for the public good. This diverse coalition has worked together for over a year to create a shared set of values, tactics, and practices to help creators and distributors use this powerful technology responsibly as it evolves.

Three Categories of Stakeholders

PAI’s Responsible Practices for Synthetic Media offers recommendations for three categories of stakeholders contributing to the societal impact of synthetic media:

and Infrastructure

and Publishers

Three Key Techniques

Based around the core concepts of consent, disclosure, and transparency, the Framework outlines key techniques for developing, creating, and sharing synthetic media responsibly.

Along with stakeholder-specific recommendations, the Framework asks organizations to:

counter the harmful use

of synthetic media

harmful uses of synthetic media

strategies when synthetic media

is used to cause harm

A Living Document

PAI’s Responsible Practices for Synthetic Media is a living document. While it is grounded in existing norms and practices, it will evolve to reflect new technology developments, use cases, and stakeholders. Responsible synthetic media, infrastructure development, creation, and distribution are emerging areas with fast-moving changes, requiring flexibility and calibration over time. PAI plans to conduct a yearly review of the Framework and also to enable a review trigger at any time as called for by the AI and Media Integrity Steering Committee.

Read the Framework

The Partnership on AI’s (PAI) Responsible Practices for Synthetic Media is a set of recommendations to support the responsible development and deployment of synthetic media.

These practices are the result of feedback from more than 100 global stakeholders. It builds on PAI’s work over the past four years with representatives from industry, civil society, media/journalism, and academia.

With this Framework, we seek to:

- Advance understanding on how to realize synthetic media’s benefits responsibly, building consensus and community around best practices for key stakeholders from industry, media/journalism, academia, and civil society

- Both offer guidance for emerging players and larger players in the field of synthetic media

- Align on norms/practices to reduce redundancy and help advance responsible practice broadly across industry and society, avoiding a race to the bottom

- Ensure that there is a document and associated community that are both useful and can adapt to developments in a nascent and rapidly changing space

- Serve as a complement to other standards and policy efforts around synthetic media, including internationally

The intended stakeholder audiences are those building synthetic media technology and tools, or those creating, sharing, and publishing synthetic media.

Several of these stakeholders will launch PAI’s Responsible Practices for Synthetic Media, formally joining this effort. These organizations will:

- Participate in the PAI community of practice

- Contribute a yearly case example or analysis that explores the Framework in technology or product practice

PAI will not be auditing or certifying organizations. This Framework includes suggested practices developed as guidance.

PAI’s Responsible Practices for Synthetic Media is a living document. While it is grounded in existing norms and practices, it will evolve to reflect new technology developments, use cases, and stakeholders. Responsible synthetic media, infrastructure development, creation, and distribution are emerging areas with fast-moving changes, requiring flexibility and calibration over time. PAI plans to conduct a yearly review of the Framework and also to enable a review trigger at any time as called for by the AI and Media Integrity Steering Committee.

Synthetic media presents significant opportunities for responsible use, including for creative purposes. However, it can also cause harm. As synthetic media technology becomes more accessible and sophisticated, its potential impact also increases. This applies to both positive and negative possibilities — examples of which we only begin to explore in this Framework. The Framework focuses on how to best address the risks synthetic media can pose while ensuring its benefits are able to be realized in a responsible way.

Further, while the ethical implications of synthetic media are vast, implicating elements like copyright, the future of work, and even the meaning of art, the goal of this document is to target an initial set of stakeholder groups identified by the PAI AI and Media Integrity community that can play a meaningful role in: (a) reducing the potential harms associated with abuses of synthetic media and promoting responsible uses, (b) increasing transparency, and (c) enabling audiences to better identify and respond to synthetic media.

For more information on the creation, goals, and continued development of PAI’s Responsible Practices for Synthetic Media, see the FAQ.

PAI’s Responsible Practices for Synthetic Media

Those building technology and infrastructure for synthetic media, creating synthetic media, and distributing or publishing synthetic media will seek to advance ethical and responsible behavior.

Here, synthetic media, also referred to as generative media, is defined as visual, auditory, or multimodal content that has been generated or modified (commonly via artificial intelligence). Such outputs are often highly realistic, would not be identifiable as synthetic to the average person, and may simulate artifacts, persons, or events. See Appendix A for more information on the Framework’s scope.

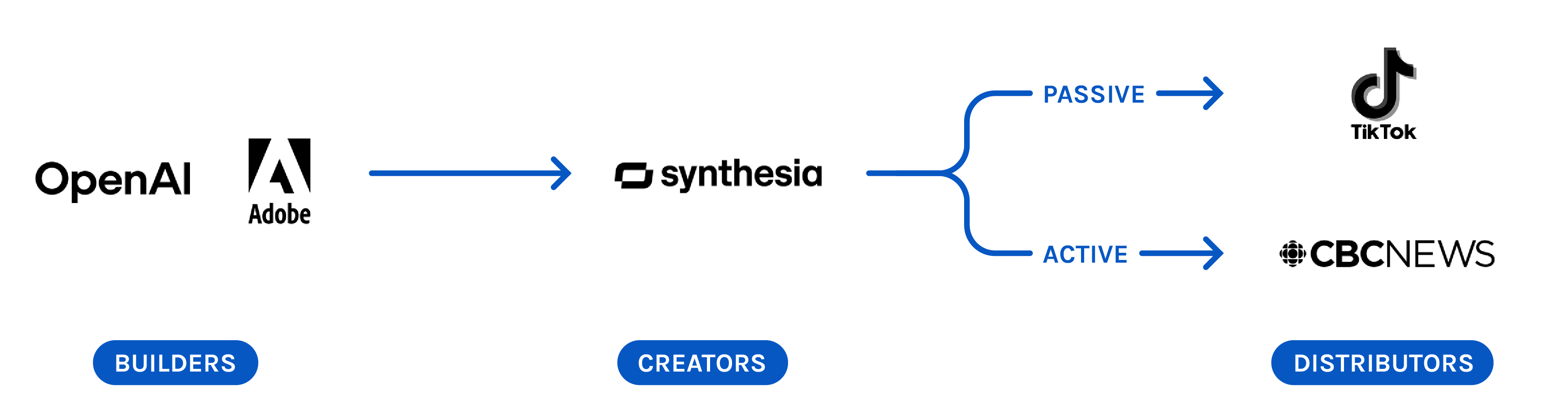

PAI offers recommendations for different categories of stakeholders with regard to their roles in developing, creating, and distributing synthetic media. These categories are not mutually exclusive. A given stakeholder could fit within several categories, as in the case of social media platforms. These categories include:

- Those building technology and infrastructure for synthetic media

- Those creating synthetic media

- Those distributing and publishing synthetic media

Section 1:

Practices for Enabling Ethical and Responsible Use of Synthetic Media

- Collaborate to advance research, technical solutions, media literacy initiatives, and policy proposals to help counter the harmful uses of synthetic media. We note that synthetic media can be deployed responsibly or can be harnessed to cause harm.

Responsible categories of use may include, but are not limited to:

- Entertainment

- Art

- Satire

- Education

- Research

- Conduct research and share best practices to further develop categories of responsible and harmful uses of synthetic media.

These uses often involve gray areas, and techniques for navigating these gray areas are described in the sections below.

- When the techniques below are deployed to create and/or distribute synthetic media in order to cause harm (see examples of harm in Appendix B), pursue reasonable mitigation strategies, consistent with the methods described in Sections 2, 3, and 4.

The following techniques can be deployed responsibly or to cause harm:

- Representing any person or company, media organization, government body, or entity

- Creating realistic fake personas

- Representing a specific individual having acted, behaved, or made statements in a manner in which the real individual did not

- Representing events or interactions that did not occur

- Inserting synthetically generated artifacts or removing authentic ones from authentic media

- Generating wholly synthetic scenes or soundscapes

For examples of how these techniques can be deployed to cause harm and an explicit, nonexhaustive list of harmful impacts, see Appendix B.

Section 2:

Practices for Builders of Technology and Infrastructure

Those building and providing technology and infrastructure for synthetic media can include: B2B and B2C toolmakers; open-source developers; academic researchers; synthetic media startups, including those providing the infrastructure for hobbyists to create synthetic media; social media platforms; and app stores.

- Be transparent to users about tools and technologies’ capabilities, functionality, limitations, and the potential risks of synthetic media.

- Take steps to provide disclosure mechanisms for those creating and distributing synthetic media.

Disclosure can be direct and/or indirect, depending on the use case and context:

- Direct disclosure is viewer or listener-facing and includes, but is not limited to, content labels, context notes, watermarking, and disclaimers.

- Indirect disclosure is embedded and includes, but is not limited to, applying cryptographic provenance to synthetic outputs (such as the C2PA standard), applying traceable elements to training data and outputs, synthetic media file metadata, synthetic media pixel composition, and single-frame disclosure statements in videos.

- When developing code and datasets, training models, and applying software for the production of synthetic media, make best efforts to apply indirect disclosure elements (steganographic, media provenance, or otherwise) within respective assets and stages of synthetic media production.

Aim to disclose in a manner that mitigates speculation about content, strives toward resilience to manipulation or forgery, is accurately applied, and also, when necessary, communicates uncertainty without furthering speculation. (Note: The ability to add durable disclosure to synthetic media is an open challenge where research is ongoing).

- Support additional research to shape future data-sharing initiatives and determine what types of data would be most appropriate and beneficial to collect and report, while balancing considerations such as transparency and privacy preservation.

- Take steps to research, develop, and deploy technologies that:

- Are as forensically detectable as possible for manipulation, without stifling innovation in photorealism.

- Retain durable disclosure of synthesis, such as watermarks or cryptographically bound provenance that are discoverable, preserve privacy, and are made readily available to the broader community and provided open source.

- Provide a published, accessible policy outlining the ethical use of your technologies and use restrictions that users will be expected to adhere to and providers seek to enforce.

Section 3:

Practices for Creators

Those creating synthetic media can range from large-scale producers (such as B2B content producers) to smaller-scale producers (such as hobbyists, artists, influencers and those in civil society, including activists and satirists). Those commissioning and creative-directing synthetic media also can fall within this category. Given the increasingly democratized nature of content creation tools, anyone can be a creator and have a chance for their content to reach a wide audience. Accordingly, these stakeholder examples are illustrative but not exhaustive.

- Be transparent to content consumers about:

- How you received informed consent from the subject(s) of a piece of manipulated content, appropriate to product and context, except for when used toward reasonable artistic, satirical, or expressive ends.

- How you think about the ethical use of technology and use restrictions (e.g., through a published, accessible policy, on your website, or in posts about your work) and consult these guidelines before creating synthetic media.

- The capabilities, limitations, and potential risks of synthetic content.

- Disclose when the media you have created or introduced includes synthetic elements especially when failure to know about synthesis changes the way the content is perceived. Take advantage of any disclosure tools provided by those building technology and infrastructure for synthetic media.

Disclosure can be direct and/or indirect, depending on the use case and context:

- Direct disclosure is viewer or listener-facing and includes, but is not limited to, content labels, context notes, watermarking, and disclaimers.

- Indirect disclosure is embedded and includes, but is not limited to, applying cryptographic provenance to synthetic outputs (such as the C2PA open standard), applying traceable elements to training data and outputs, synthetic media file metadata, synthetic media pixel composition, and single-frame disclosure statements in videos.

Aim to disclose in a manner that mitigates speculation about content, strives toward resilience to manipulation or forgery, is accurately applied, and also, when necessary, communicates uncertainty without furthering speculation.

Section 4:

Practices for Distributors and Publishers

Those distributing synthetic media include both institutions with active, editorial decision-making around content that mostly host first-party content and may distribute editorially created synthetic media and/or report on synthetic media created by others (i.e., media institutions, including broadcasters) and online platforms that have more passive displays of synthetic media and host user-generated or third-party content (i.e., social media platforms).

For both active and passive distribution channels

- Disclose when you confidently detect third-party/user-generated synthetic content.

Disclosure can be direct and/or indirect, depending on the use case and context:

- Direct disclosure is viewer or listener-facing, and includes, but is not limited to, content labels, context notes, watermarking, and disclaimers.

- Indirect disclosure is embedded and includes, but is not limited to, applying cryptographic provenance (such as the C2PA open standard) to synthetic outputs, applying traceable elements to training data and outputs, synthetic media file metadata, synthetic media pixel composition, and single-frame disclosure statements in videos.

Aim to disclose in a manner that mitigates speculation about content, strives toward resilience to manipulation or forgery, is accurately applied, and also, when necessary, communicates uncertainty without furthering speculation.

- Provide a published, accessible policy outlining the organization’s approach to synthetic media that you will adhere to and seek to enforce.

For active distribution channels

Channels (such as media institutions) that mostly host first-party content and may distribute editorially created synthetic media and/or report on synthetic media created by others.

- Make prompt adjustments when you realize you have unknowingly distributed and/or represented harmful synthetic content.

- Avoid distributing unattributed synthetic media content or reporting on harmful synthetic media created by others without clear labeling and context to ensure that no reasonable viewer or reader could take it to not be synthetic.

- Work towards organizational content provenance infrastructure for both non-synthetic and synthetic media, while respecting privacy (for example, through the C2PA open standard).

- Ensure that transparent and informed consent has been provided by the creator and the subject(s) depicted in the synthetic content that will be shared and distributed, even if you have already received consent for content creation.

For passive distribution channels

Channels (such as platforms) that mostly host third-party content.

- Identify harmful synthetic media being distributed on platforms by implementing reasonable technical methods, user reporting, and staff measures for doing so.

- Make prompt adjustments via labels, downranking, removal, or other interventions like those described here, when harmful synthetic media is known to be distributed on the platform.

20. Clearly communicate and educate platform users about synthetic media and what kinds of synthetic content are permissible to create and/or share on the platform.

Appendices

While this Framework focuses on highly realistic forms of synthetic media, it recognizes the threshold for what is deemed highly realistic may vary based on an audience’s media literacy and across global contexts. We also recognize that harms can still be caused by synthetic media that is not highly realistic, such as in the context of intimate image abuse. This Framework has been created with a focus on audiovisual synthetic media, otherwise known as generative media, rather than synthetic text which provides other benefits and risks. However, it may still provide useful guidance for the creation and distribution of synthetic text.

Additionally, this Framework only covers generative media, not the broader category of generative AI as a whole. We recognize that these terms are sometimes treated as interchangeable.

Synthetic media is not inherently harmful, but the technology is increasingly accessible and sophisticated, magnifying potential harms and opportunities. As the technology develops, we will seek to revisit this Framework and adapt it to technological shifts (e.g., immersive media experiences).

List of potential harms from synthetic media we seek to mitigate:

- Impersonating an individual to gain unauthorized information or privileges

- Making unsolicited phone calls, bulk communications, posts, or messages that deceive or harass

- Committing fraud for financial gain

- Disinformation about an individual, group, or organization

- Exploiting or manipulating children

- Bullying and harassment

- Espionage

- Manipulating democratic and political processes, including deceiving a voter into voting for or against a candidate, damaging a candidate’s reputation by providing false statements or acts, influencing the outcome of an election via deception, or suppressing voters

- Market manipulation and corporate sabotage

- Creating or inciting hate speech, discrimination, defamation, terrorism, or acts of violence

- Defamation and reputational sabotage

- Non-consensual intimate or sexual content

- Extortion and blackmail

- Creating new identities and accounts at scale to represent unique people in order to “manufacture public opinion”

Learn More

What Is Synthetic Media?

Synthetic media, also referred to as generative media, is visual, auditory, or multimodal content that has been artificially generated or modified (commonly through artificial intelligence). Such outputs are often highly realistic, would not be identifiable as synthetic to the average person, and may simulate artifacts, persons, or events.

Part 1: Framing the Responsible Practices

PAI’s Responsible Practices for Synthetic Media: A Framework for Collective Action is a set of recommendations to support the responsible development and deployment of synthetic media. The intended audiences are those creating synthetic media technology and tools or creating, sharing, and publishing synthetic media content. The Framework builds on PAI’s work over the past four years with industry, civil society, media/journalism, and academia to evaluate the challenges and opportunities for synthetic media.

- Advance understanding on how to realize synthetic media’s benefits responsibly, building consensus and community around best practices for key stakeholders from industry, media/journalism, academia, and civil society

- Both offer guidance for emerging players and larger players in the field of synthetic media

- Align on norms/practices to reduce redundancy and help advance responsible practice broadly across industry and society, avoiding a race to the bottom

- Ensure that there is a document and associated community that are both useful and can adapt to developments in a nascent and rapidly changing space

- Serve as a complement to other standards and policy efforts around synthetic media, including internationally

What PAI is not doing:

- Auditing or certifying organizations

Think of this document like a constitution, not a set of laws. We provide recommendations to ensure that the emerging space of responsible synthetic media has a set of values, tactics, and practices to explore and evaluate. This document reflects the fact that responsible synthetic media (and its associated infrastructure development, creation, and distribution) is an emerging area with fast-moving developments requiring flexibility and calibration over time.

Synthetic media presents significant opportunities for responsible use, including for creative purposes. However, it can also cause harm. As synthetic media technology becomes more accessible and sophisticated, its potential impact also increases. This applies to both positive and negative possibilities — examples of which we only begin to explore in this Framework. The Framework focuses on how to best address the risks synthetic media can pose while ensuring its benefits are able to be realized in a responsible way.

We recognize, however, that many institutions collaborating with us are explicitly working in the creative and responsible content categories. In the Framework, we include a list of harmful and responsible content categories, and we explicitly state that this list is not exhaustive, often includes gray areas, and that specific elements of the Framework apply to responsible use cases as well.

This Framework has been created with a focus on visual, auditory, or multimodal content that has been generated or modified (commonly via artificial intelligence). Such outputs are often highly realistic, would not be identifiable as synthetic to the average person, and may simulate artifacts, persons, or events. However, the Framework may still provide useful guidance for the creation and distribution of synthetic text.

Additionally, this Framework focuses on highly realistic forms of synthetic media, but recognizes the threshold for what is deemed highly realistic may vary based on audience’s media literacy and across global contexts. We also recognize harms can still be caused by synthetic media that is not highly realistic, such as in the context of intimate image abuse. In addition, this Framework only covers generative media, not the broader category of generative AI as a whole. We recognize that these terms are sometimes treated as interchangeable.

Part 2: Involvement in the Framework

- Joining/Continuing Participation in the Framework Community of Practice. Agreement to join a synthetic media community of good-faith actors working to develop and deploy responsible synthetic media while learning together about this emerging technology, facilitated by PAI.

- Transparency via Case Contribution. Commitment to explore case examples or analysis related to the application of the Framework with the PAI synthetic media community — through a pilot and/or reporting of a case example via an annual public reporting process.

- Convening Participation. Agreement to participate in one to two programmatic convenings in 2023 evaluating the Framework’s use for real-world case examples and evolution of the synthetic media field. These are an opportunity to share about learnings from applying the Framework with others in the community.

PAI developed the Responsible Practices for Synthetic Media from January 2022 to January 2023, through:

- Bilateral meetings with stakeholders

- Public comment submissions

- Meetings with the AI and Media Integrity Steering Committee (every two weeks)

- Meetings with the Framework Working Group (every two weeks)

- Program Meetings with the AI and Media Integrity Program Members (three meetings)

- Additional convenings with the DARPA/NYU Computational Disinformation Working Group and a Synthetic Media Startup Cohort

Development timeline, 2022

Part 3: The Framework as a Living Document

One of the expectations of Framework supporters is the submission of a case example, in which the organization reflects on how the Framework can be applied to a synthetic media challenge it has faced or is currently facing. By collecting real-world examples of use cases to pressure test the Framework against, we can see how the Framework principles stand up against technological advancements and public understanding of AI-generated and modified content.

Those that join the Framework effort will explore case examples or analysis related to the application of its recommendations as part of the Framework Community of Practice. Over the course of each year, PAI will host convenings where the community applies the Framework to these cases, as well as additional public cases identified by PAI staff. The 11 case studies we published in March 2024 provide industry, policy makers, and the general public with a shared body of case material that puts the Framework into practice. These case studies allow us to pressure test the Framework and to further operationalize its recommendations via multistakeholder input, especially when applied to gray areas. The case studies also provide us with opportunities to identify what areas of the Framework can be improved upon to better inform audiences.

Although regulation and government policy are emerging in the synthetic media space, the Framework exemplifies a type of norm development and public commitment that can help to strengthen the connection between policies, entities, and industries that are relevant to responsible synthetic media. While we have intentionally limited the involvement of policymakers in drafting the Framework, we have thought about its development as a complement to existing and forthcoming regulation, as well as intergovernmental and organizational policies on AI, mis/disinformation, and synthetic and generative media. For example, we have thought about the Framework alongside the EU AI Act, the EU Code of Practice on Disinformation, as well as the launch of the Deepfake Task Force Act in the U.S. Following the launch of the Framework, we plan to engage the policy community working on and around AI, mis/disinformation, and synthetic and generative media policy, including through a policymaker roundtable on the Framework in 2023.

Part 4: Development Process

PAI worked with over 50 global institutions in a participatory, year-long drafting process to create the current Responsible Practices for Synthetic Media. Participating stakeholders included the broader AI and media integrity field of synthetic media startups, social media platforms, AI research organizations, advocacy and human rights groups, academic institutions, experiential experts, news organizations, and public commenters.

Development timeline, 2022

The Framework is not a static document, but a living one. You can think of the Framework like a constitution, and not a set of laws, providing the burgeoning generative AI space with a set of guidelines for ethical synthetic media. PAI will revise the Framework each year in order to reflect new technology developments, use cases, and stakeholders.Part of that evolution will be informed by case examples from the real-world institutions building, creating, and sharing synthetic media. Institutions that join the Responsible Practices for Synthetic Media will provide yearly reports or analysis on synthetic media cases and how the Framework can be explored in practice. These cases will be published and inform the evolution of synthetic media policymaking and AI governance.

Case Studies

The best practices outlined in PAI’s Synthetic Media Framework will need to evolve with both the technology and information landscape. Thus, to understand how the principles can be applied to the real-world, we required all 18 of the Framework supporters to submit an in-depth case study exploring how they implemented the Framework in practice.

In March 2024, ten Framework supporters delivered case studies, with PAI drafting one of our own. This set of case studies, and the accompanying analysis, focused on transparency, consent, and harmful/responsible use cases.

In November 2024, another five Framework supporters developed case studies, specifically focused on an underexplored area of synthetic media governance: direct disclosure — methods to convey to audiences how content has been modified or created with AI, like labels or other signals — and PAI developed policy recommendations based on insights from the cases.

The cases not only provide greater transparency on institutional practices and decisions related to synthetic media, but also help the field refine policies and practices for responsible synthetic media, including emergent mitigations. Importantly, the cases may support AI policymaking overall, providing broader insight about how collaborative governance can be applied across institutions.

Read PAI’s takeaways and recommendations from the case studies

Group 1

Read PAI’s analysis of these cases

Read Adobe’s case study

Read CBC Radio-Canada’s case study

Read D-ID’s case study

Read Respeecher’s case study

Read Synthesia’s case study

Read TikTok’s case study

Read WITNESS’s case study

Read PAI’s case study

Group 2

Read PAI’s policy recommendations from these cases

Read Code for Africa’s case study

Read Meedan’s case study

Read Microsoft’s case study

Read the HAI researchers’ case study

Read Thorn’s case study

Read Truepic’s case study

The case submitting organizations are a seemingly eclectic group; and yet they’re all integral members of a synthetic media ecosystem that requires a blend of technical and humanistic might to benefit society.

Some of those featured are Builders of technology for synthetic media, while others are Creators, or Distributors. Notably, while civil society organizations are not typically creating, distributing, or building synthetic media (though that’s possible), they are included in the case process; they are key actors in the ecosystem surrounding digital media and online information who must have a central role in AI governance development and implementation.

Partnership on AI

Partnership on AI